Forecasting reflections from GHACOF 57

The GHACOF is a key part of climate services in the Greater Horn of Africa, and will be a cornerstone of dissemination of DOWN2EARTH activity to stakeholders.

But what is the GHACOF?

In this blog post we explain the GHACOF and review this years event. Along with this we provide a explainer, to help understand this year’s forecast.

The GHACOF

On 17th February, an objective seasonal forecast was released at the 57th GHACOF (Greater Horn of Africa Regional Climate Outlook Forum).

At the GHACOF representatives from the National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHS) of the countries of the region come together to construct and release an objective seasonal forecast. They base the forecast on a range of inputs, including state-of-the art dynamical seasonal forecast models run at mandated global producing centres.

The GHACOF is co-ordinated by the IGAD Climate Prediction and Application Centre (ICPAC), the WMO-accredited Regional Climate Centre of excellence, with a mandate for providing climate services to national and regional users of Eastern Africa. The GHACOFs are a core part of ICPAC engagement with stakeholders and occur three times a year in advance of each of the three rainfall seasons. Interaction with stakeholders at GHACOF is focused around several sectoral workshops and new co-production sessions, focusing on topics ranging from agriculture and food security to conflict early warning.

Of course like everything else recently GHACOF 57 has moved online whilst international travel restrictions are in place. Nevertheless, many of the team from DOWN2EARTH attended GHACOF 57. DOWN2EARTH presence at the event was headed by Michael Singer, who presented the project at the main plenary, whilst many others from across the team were involved across all the range of co-production and sectoral meetings.

It isn’t all about the forecast

Producing the forecast is the primary but not the only purpose of the GHACOF. In the week before main event, the so-called ‘Pre COF’ is held. It is here that the NMHS representatives convene to produce the forecast. But it is also an effort in capacity building, with experts from ICPAC and international partners working together with NMHS forecasters, providing training in understanding predictability and developing the technical skills needed to work with and calibrate forecast data. Forecasters can then take these skills back to NMHS helping to build long-term capacity in forecasting.

What is the outlook for this season?

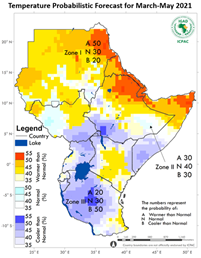

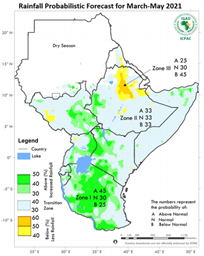

GHACOF 57 focused on the March-April-May rainy season, and this year’s forecast can be seen here.

The forecast groups the region into different ‘Zones’; in each zone a similar outlook is given. For this season three Zones have been suggested. Zone 1 covers Tanzania, West Kenya and parts of Uganda, South Sudan and Ethiopia and indicates enhanced chance of wet conditions. On the other hand Zone 3 covers northern Ethiopia and indicates enhanced chance of dry conditions. In between, Zone 2 covers the rest of the region including most of Somalia, eastern Kenya and Ethiopia. The forecast here is for ‘normal probabilities’.

What does ‘normal probabilities mean’?

The GHACOF objective rainfall forecast is always presented with three numbers. In this case most of the region shows 33/33/33. What does that mean? These three numbers refer to the probability that next season’s rainfall total will be classified as “Above Normal” (AN), “Near Normal” (NN) or “Below Normal” (BN) respectively. The categories are defined by ranking historical seasonal totals from wettest to driest and diving into three equal parts (known as terciles). The long term probability of seasonal total falling in any particular category is 33%. So when we see a forecast of 33/33/33, it means that probabilities are unchanged from the baseline risk.

To make an analogy: each season is like rolling a dice.

Let’s say if you get a five or six the seasonal total will be AN. Three or four gets you NN and with one or two you get BN. Now, sometimes nature hands you a biased dice ahead of the season. Perhaps the “one” has been changed to a “five”, so that the chance of AN is now 50% and BN is 17%; with this new dice the tercile probabilities are 50/33/17. This is the kind of thing you would see in the “short rains”; in this season (October-December), seasonal total is highly influenced by predictable large-scale climate drivers so these shifts in probability can often be anticipated.

However March-May is the “long rains” and in this season evidence suggests that predictability is more limited (although some research has shown that in recent years droughts have become more predictable, Funk et al 2018). That means it may be difficult to be confident about strong departures from “normal probabilities”. In any case signals arising from seasonal climate models are generally quite weak. Furthermore research has shown that when models do show stronger signals for the long rains the probabilities are not particularly reliable.

So for next season, probabilities are “normal” for most of the region. However this does not mean “expect a normal season”. This misinterpretation is unfortunately quite common, e.g. “the forecast is for normal conditions, and so prospects for extreme impacts are reduced”. In fact the exact opposite is true! With a forecast of 33/33/33 the chance of an unusually wet season is just as high as normal - as is the chance of an unusually dry season! One way of reframing a 33/33/33 forecast is that is indicates high uncertainty in outcomes.

With this in mind, it was great to see ICPAC highlighting this uncertainty in the presentation of their forecast; when discussing the 33/33/33 region, the advice was given to stakeholders to ensure they have contingency plans for any eventuality. To be clear, this is not ICPAC covering their back, or hedging their bets. It is an honest and scientifically informed estimate of future risks based on the forecast information they have.

The bottom line: making precise statements about the future is only justified when evidence supports it. In this case, a forecast of “normal probabilities” may be the best that can be done.

Communicating uncertainty in forecasts is a challenge. To answer it, capacity building and training at National Meteorological and Hydrological Services is crucial, and the GHACOF (along with its satellite workshops) are an essential part of these efforts.